Repaglinide vs Diabetes Drug Comparison Tool

Medication Comparison Details

- Dosage: Before each main meal (2-3×/day)

- Onset: 15-30 min

- Duration: 2-4 hours

- Hypoglycemia Risk: Moderate

- Weight Impact: Neutral

- Cost: £8-£12/month

- Dosage: Once daily

- Onset: 24 hours steady state

- Duration: Long-term

- Hypoglycemia Risk: Very Low

- Weight Impact: Neutral

- Cost: £30-£40/month

- Dosage: Once daily

- Onset: 1-2 hours

- Duration: Up to 24 hours

- Hypoglycemia Risk: High

- Weight Impact: Weight Gain (~2-3 kg)

- Cost: £5-£9/month

- Dosage: Once daily

- Onset: 1-2 hours

- Duration: 24 hours

- Hypoglycemia Risk: Low

- Weight Impact: Weight Loss (~1-2 kg)

- Cost: £35-£45/month

Key Takeaways

- Repaglinide works fast, ideal for meals, but needs multiple daily doses.

- Newer classes (DPP‑4, SGLT2, GLP‑1) lower blood sugar with less hypoglycaemia risk.

- Sulfonylureas are cheaper but carry higher weight‑gain and hypoglycaemia rates.

- Choose based on lifestyle, kidney function, cost, and personal tolerance.

- Always discuss switches with a prescriber - a small change can affect long‑term control.

When you hear the name Repaglinide is a short‑acting meglitinide that stimulates insulin release after meals. It’s sold under the brand Prandin and has been used for type 2 diabetes since the early 2000s. If you’re hunting for Prandin alternatives, you’re probably weighing how it stacks up against older sulfonylureas, newer oral agents, and injectable GLP‑1 therapies.

How Repaglinide Works

Repaglinide binds to the potassium channel on pancreatic β‑cells, prompting a rapid insulin surge that peaks within 15‑30minutes after a meal. Its effect fades after 2‑4hours, so you take it before each main meal. Because it’s short‑acting, the risk of overnight hypoglycaemia is lower than with long‑acting sulfonylureas, yet it still requires timing precision.

Core Comparison Table

| Drug (Class) | Typical Dose Frequency | Onset / Duration | Hypoglycaemia Risk | Weight Impact | Key Cost (UK, 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repaglinide Meglitinide |

Before each main meal (2‑3×/day) | 15‑30min onset, 2‑4h duration | Low to moderate | Neutral | £8‑£12 per month |

| Nateglinide Meglitinide |

Before each meal (3×/day) | 30‑45min onset, 4‑6h duration | Low | Neutral | £10‑£14 per month |

| Glipizide Sulfonylurea |

Once daily | 1‑2h onset, up to 24h duration | High (especially in elderly) | Weight gain (≈2‑3kg) | £5‑£9 per month |

| Sitagliptin DPP‑4 inhibitor |

Once daily | 24h steady state | Very low | Weight neutral | £30‑£40 per month |

| Empagliflozin SGLT2 inhibitor |

Once daily | Onset 1‑2h, lasts 24h | Low (but risk of genital infection) | Modest weight loss (≈1‑2kg) | £35‑£45 per month |

| Liraglutide GLP‑1 receptor agonist (injectable) |

Daily injection | Gradual reduction, long‑term effect | Very low | Weight loss (≈3‑5kg) | £120‑£150 per month |

When Repaglinide Makes Sense

Because the drug works only when you eat, it’s a good match for people who have irregular meal patterns - shift workers, retirees who snack often, or anyone who needs flexibility. It also fits patients who can’t tolerate sulfonylureas because of frequent low‑blood‑sugar episodes. However, the need to remember a pre‑meal pill can be a hassle if you’re forgetful.

Alternative Classes Broken Down

Meglitinides (Nateglinide): Almost identical to Repaglinide but with a slightly longer half‑life. If you prefer a drug that tolerates a bit more spacing between meals, Nateglinide can be an option, though it’s less widely available in the UK.

Sulfonylureas (Glipizide, Gliclazide): Cheaper, once‑daily dosing, but they stay active for many hours, raising the odds of hypoglycaemia, especially overnight. They also tend to cause weight gain, which some patients find unacceptable.

DPP‑4 inhibitors (Sitagliptin, Linagliptin): Oral, once‑daily, virtually no hypoglycaemia when used alone, and they’re weight neutral. The trade‑off is higher cost and a modest glucose‑lowering effect (≈0.5‑0.8% HbA1c reduction).

SGLT2 inhibitors (Empagliflozin, Dapagliflozin): Provide glucose loss via urine, lower blood pressure, and aid weight loss. They have a small risk of urinary‑tract infections and aren’t recommended for patients with severe kidney impairment.

GLP‑1 receptor agonists (Liraglutide, Semaglutide): The most potent at dropping HbA1c (up to 1.5%). They also promote weight loss and have cardiovascular benefits, but they require injection and are the priciest option.

Decision Guide: Picking the Right Agent

- Meal timing flexibility? Choose Repaglinide or Nateglinide.

- Budget constraints? Sulfonylureas are cheapest; consider generic glipizide.

- Concern about low blood sugar? DPP‑4, SGLT2, or GLP‑1 agents have the lowest risk.

- Need weight loss? SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP‑1 agonists are best.

- Kidney function intact? SGLT2 need eGFR≥45mL/min/1.73m²; otherwise stick with Repaglinide or sulfonylureas.

In practice, many clinicians start with a cheap sulfonylurea, add a DPP‑4 for safety, and switch to an SGLT2 or GLP‑1 if cardiovascular risk rises.

Safety Profile & Common Side Effects

All oral agents can cause gastrointestinal upset, but the patterns differ:

- Repaglinide/Nateglinide: mild nausea, occasional headache, hypoglycaemia if meals are skipped.

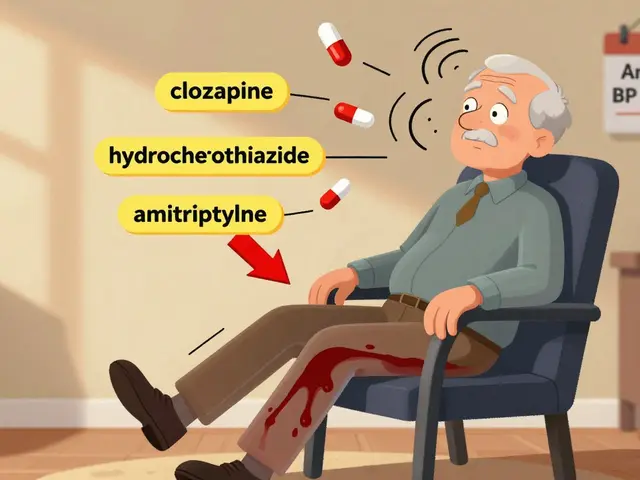

- Sulfonylureas: higher hypoglycaemia, weight gain, rare skin rash.

- DPP‑4 inhibitors: nasopharyngitis, rarely pancreatitis.

- SGLT2 inhibitors: genital fungal infections, dehydration, rare ketoacidosis.

- GLP‑1 agonists: nausea, vomiting, possible gallbladder disease.

Always review kidney function, liver enzymes, and current meds to avoid dangerous interactions - for example, combining Repaglinide with strong CYP2C8 inhibitors (like gemfibrozil) can boost drug levels and raise hypoglycaemia risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take Repaglinide with a sulfonylurea?

Mixing two insulin‑secretagogues is generally avoided because it sharply raises hypoglycaemia risk. If tighter control is needed, doctors usually add a drug from a different class (e.g., a DPP‑4 inhibitor) instead.

Do I need to take Repaglinide every day?

Only on days you eat a main meal. Because it works fast and clears quickly, missing a dose on a low‑calorie day won’t cause lingering low blood sugar.

Is Repaglinide safe for people over 70?

It can be used, but dose reduction and close monitoring are advised. Age‑related kidney decline can affect drug clearance, and older adults are more prone to hypoglycaemia.

How does Repaglinide compare to Sitagliptin for A1c reduction?

Repaglinide typically drops A1c by 0.8‑1.2% if taken with meals, while Sitagliptin offers about 0.5‑0.8% reduction. The choice hinges on hypoglycaemia tolerance and cost.

Can I switch from Repaglinide to an SGLT2 inhibitor?

Yes. Doctors usually taper the meglitinide while starting the SGLT2, monitoring blood glucose to avoid gaps in control.

14 Comments

Pharma often spouts glossy language to disguise underlying motives.

Take charge of your diabetes regimen; pick a drug that fits your life and stick with it.

If you’re juggling erratic meals, Repaglinide can be a solid ally. It spikes insulin right when you need it, so you don’t have to worry about overnight lows. Pair it with a consistent carb count and you’ll see steadier glucose trends. Remember, any medication should be tailored with your doctor’s guidance.

Yo Frank, ur take sounds a bit over‑the‑top. The data actually shows Repaglinide has a moderate hypoglycemia risk, not “propaganda”. Also, the cost comparison you tossed in is accurate for UK pricing. Let’s keep the debate factual, not rhetorical.

While your encouragement is appreciated, it is vital to underscore the pharmacokinetic nuances of short‑acting meglitinides. The rapid onset necessitates precise pre‑meal timing, which may pose adherence challenges for certain patient cohorts. Moreover, clinicians must evaluate renal function before initiation. A balanced view of benefits versus logistical constraints is essential.

There’s a hidden agenda behind every glossy drug brochure you see on the internet.

Big Pharma loves to push the narrative that newer oral agents are flawless miracles.

But the truth is buried in the fine print of clinical trial disclosures.

Repaglinide, for instance, was quietly marketed as a “flexible” solution while manufacturers knew many patients would miss doses and crash.

They even funded key opinion leaders to sing its praises at conferences, drowning out dissenting voices.

When you look at the data, the hypoglycemia rates are not negligible, especially in the elderly.

And the cost, though seemingly modest, adds up when you factor in the need for multiple daily pills.

Meanwhile, the newer classes like SGLT2 inhibitors come with hidden risks of infections that are downplayed.

Your enthusiasm for any medication must be tempered by a healthy dose of skepticism.

Ask yourself why the FDA fast‑tracks certain drugs while keeping others in limbo.

The answer often lies in who is paying the lobbying bills.

Patients deserve transparency, not a one‑size‑fits‑all hype machine.

So before you jump on the Repaglinide bandwagon, dig deeper into the real-world evidence.

Read the patient‑reported outcomes, not just the manufacturer's summary.

Only then can you make an informed choice that isn’t manipulated by corporate interests.

Indeed, one must consider the ethical implications of prescribing a drug that demands such precise timing; the burden placed on patients may be deemed unreasonable; accountability lies with clinicians to prioritize safety above convenience.

It could be argued that the timing requirement is simply a matter of patient education rather than an ethical failing; after all, many medications have dosing complexities.

i dont see why anyone would pick repaglinide over cheaper sulfonylureas.

While cost considerations are undeniably important, it is essential to weigh them against clinical efficacy and hypoglycemia risk, which differ markedly between meglitinides and sulfonylureas.

The ontological distinction between ‘effectiveness’ and ‘efficacy’ often blurs in popular discourse on antidiabetic agents. In the context of Repaglinide, efficacy refers to its capacity to reduce postprandial glucose spikes, whereas effectiveness encompasses real‑world adherence and safety outcomes. Empirical studies have shown a modest HbA1c reduction, yet patient‑reported hypoglycemia episodes remain a concern. By contrast, DPP‑4 inhibitors deliver steadier glucose control with minimal hypoglycemia, albeit at higher monetary expense. Thus, the choice is a dialectic between pharmacodynamic precision and holistic patient experience. A nuanced, evidence‑based approach should guide therapeutic decisions.

Allow me to dissect the prevailing narrative that elevates short‑acting agents to near‑mythic status. The allure of rapid insulin surges masks a cascade of potential pitfalls, from missed doses to nocturnal hypoglycemia that can be fatal. Moreover, the pharmaceutical lobby has masterfully scripted a story where convenience eclipses safety, luring clinicians into prescribing without rigorous scrutiny. One must question why such a drug, burdened with multiple daily administrations, is still championed despite the existence of once‑daily alternatives with comparable efficacy. The literature is replete with case reports of elderly patients succumbing to unintended low blood sugars, yet these anecdotes are buried beneath glossy marketing decks. Furthermore, the economic calculus of “£8‑£12 per month” neglects indirect costs such as frequent glucose testing and medical visits stemming from adverse events. In my view, the ethical dilemma lies in promoting a therapy that trades patient autonomy for pharmaceutical profit. The medical community bears responsibility to illuminate these hidden hazards. Only through transparent dialogue can we dismantle the mythos surrounding Repaglinide. Let us champion an evidence‑first paradigm, free from corporate coercion.

From my perspective, the conversation around diabetes medications often forgets the human element behind the data. People with type 2 diabetes juggle work, families, and unpredictable meal schedules, so flexibility isn’t just a perk-it’s a lifeline. Repaglinide offers that rapid, meal‑timed insulin boost, which can be liberating for shift workers or those who crave spontaneity. Yet, we must also acknowledge that the discipline required to remember multiple daily doses can be a hurdle for many. Balancing cost, side‑effect profiles, and personal lifestyle is a deeply individual journey. Ultimately, the best drug is the one that seamlessly integrates into one’s daily rhythm while keeping blood sugars stable and the wallet intact.

Spot on, Jackie. When counseling patients, I always start by mapping their daily routine and then match it to a drug’s dosing schedule; Repaglinide works well for those with irregular meals, but I steer the budget‑concerned toward sulfonylureas or consider insurance coverage options for newer agents.