Kernicterus Risk Calculator

This calculator assesses the risk of kernicterus in newborns based on bilirubin level, albumin level, and medications used. Kernicterus occurs when bilirubin crosses the blood-brain barrier and causes permanent neurological damage. The risk increases when bilirubin displaces from albumin due to certain medications.

Risk Assessment

- Bilirubin level: mg/dL

- Albumin level: g/dL

- Medications:

Recommended Action

Prevention Tips

When a newborn turns yellow, it’s common. Jaundice affects up to 60% of full-term babies in the first week of life. Most cases are harmless and fade on their own. But in rare cases, that yellow tint can be a warning sign of something far more dangerous: kernicterus. This is not just severe jaundice. It’s brain damage caused by too much bilirubin slipping into the brain tissue - and it’s almost always preventable. The biggest preventable trigger? Certain medications, especially sulfonamides.

What Exactly Is Kernicterus?

Kernicterus happens when unconjugated bilirubin, a natural byproduct of red blood cell breakdown, builds up past safe levels. In adults, the liver easily processes it. In newborns, especially those under 2 weeks old, the liver isn’t fully ready. That’s why bilirubin climbs. Normally, it binds to albumin - a protein in the blood - and gets carried safely to the liver. But some drugs break that bond. When they do, free bilirubin floats around, crosses the immature blood-brain barrier, and stains the brain’s nuclei. The result? Permanent neurological damage. Hearing loss, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability. These aren’t theoretical risks. They’re real outcomes documented in hospital records and malpractice cases.The term comes from "kern" (kernel) and "icterus" (jaundice), referring to the yellow staining seen in brain nuclei under the microscope. It was first described over 120 years ago, but we still see preventable cases today - not because parents ignored jaundice, but because medication was given without checking the bilirubin level.

Why Sulfonamides Are So Dangerous

Sulfonamides - like sulfisoxazole and sulfamethoxazole - were once common antibiotics for newborns. Today, they’re rarely used, but they still pop up. In rural clinics, in developing countries, or when doctors aren’t aware of the risk, they’re prescribed for urinary tract infections, ear infections, or even just as prophylaxis.Here’s the science behind the danger: sulfonamides compete with bilirubin for binding sites on albumin. At therapeutic doses, they displace 25-30% of bilirubin from its safe carrier. That means even if a baby’s total bilirubin level looks "normal" - say, 12 mg/dL - the free bilirubin might be high enough to cause brain injury. Studies show this displacement can push free bilirubin over the danger threshold of 10 mcg/dL within hours.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clearly lists sulfonamides as a high-risk medication. Their 2022 guidelines say: avoid them entirely if bilirubin is above 75% of the phototherapy threshold. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a rule. One dose. One hour. One baby. That’s all it takes.

Other Medications That Can Trigger Kernicterus

Sulfonamides aren’t alone. Other drugs carry similar risks:- Ceftriaxone - A common IV antibiotic. Displaces 15-20% of bilirubin. Risk increases in infants with low albumin or acidosis.

- Aspirin (salicylates) - Never give aspirin to a newborn. Even baby aspirin can be dangerous. It displaces bilirubin and increases bleeding risk.

- Furosemide - A diuretic sometimes used for fluid overload. Can reduce albumin binding and worsen bilirubin toxicity.

- Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) - A combination drug still used in some settings. The sulfonamide component is the problem.

These aren’t rare side effects. They’re well-documented, predictable drug interactions. A 2023 AAFP review found sulfonamides increase the risk of severe hyperbilirubinemia by 3.2 times compared to safer antibiotics like amoxicillin-clavulanate. Ceftriaxone? 1.8 times higher risk. The numbers don’t lie.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not all newborns are equally vulnerable. The highest risk group includes:- Babies with bilirubin levels near or above the phototherapy threshold

- Preterm infants (under 37 weeks) - their livers are weaker, and albumin levels are lower

- Infants with G6PD deficiency - this genetic condition affects 7% of the global population and causes red blood cells to break down faster, spiking bilirubin

- Babies with acidosis or dehydration - these conditions reduce albumin’s ability to bind bilirubin

- Infants with feeding problems - poor intake leads to less stooling, which means less bilirubin is excreted

Here’s a hard truth: a baby can have a "normal" bilirubin level and still be at risk. That’s because the danger isn’t just the total number. It’s how much is free and unbound. That’s why checking albumin levels matters. If albumin is below 3.0 g/dL, even moderate bilirubin becomes dangerous.

Real Cases, Real Consequences

In 2022, a nurse practitioner in Texas posted on an AAP forum about a 5-day-old infant with a bilirubin level of 14.2 mg/dL. The baby was given sulfisoxazole for UTI prophylaxis. Within 12 hours, the bilirubin jumped to 22.7 mg/dL. The infant needed intensive phototherapy and nearly required an exchange transfusion - a last-resort procedure where the baby’s blood is swapped to remove bilirubin.On Reddit’s neonatology community, a resident described a kernicterus case in a late preterm infant given Bactrim for suspected sepsis. The baby had mild jaundice. The parents weren’t warned. The baby later developed hearing loss and motor delays. The family received a $4.2 million settlement. That’s not an outlier. The Birth Injury Justice Center reports that 12% of all kernicterus malpractice cases involve inappropriate sulfonamide use.

These aren’t mistakes made by bad doctors. They’re system failures. A 2022 survey of pediatric residents found it takes about six months of clinical experience to reliably recognize these risks. Many new doctors don’t know the connection between antibiotics and bilirubin.

How to Prevent It

The good news? Kernicterus is almost 100% preventable. Here’s what works:- Check bilirubin before giving any antibiotic. If the level is above 75% of the phototherapy threshold for the baby’s age, avoid sulfonamides and other displacing drugs.

- Test albumin levels if the baby is preterm, sick, or has low intake. Albumin under 3.0 g/dL means even lower bilirubin levels are risky.

- Screen for G6PD deficiency in high-risk populations (Southeast Asian, African, Mediterranean descent). If positive, avoid all sulfonamides.

- Use safer alternatives. Amoxicillin-clavulanate, penicillin, or cephalosporins (non-ceftriaxone) are much safer. They don’t displace bilirubin.

- Use automated alerts. Hospitals with electronic health records (EHR) that block sulfonamide orders when bilirubin is high have cut kernicterus cases by 87%. Epic Systems added this alert in late 2023.

The AAP’s free Bilirubin Exposure Risk Calculator - updated in March 2023 - now includes medication risk factors. It’s not just for specialists. Any clinician managing a jaundiced newborn should use it.

Why This Still Happens

You might wonder: if we’ve known about this since the 1950s, why are we still seeing cases? Three reasons:- Cost. In some countries, sulfonamides cost $0.05 per dose. Safer antibiotics cost $2.50. When resources are tight, cheaper wins - even when it kills.

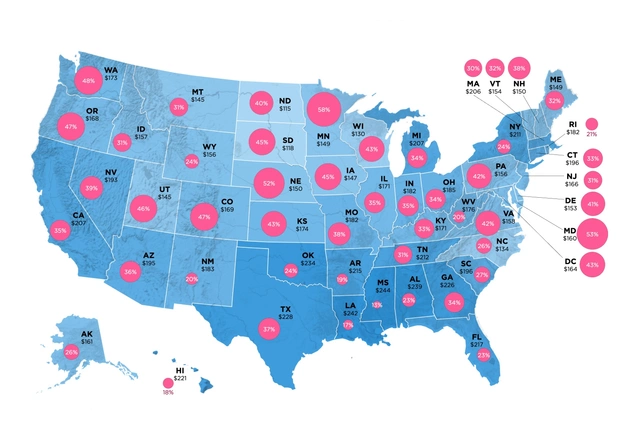

- Lack of testing. 23% of rural U.S. hospitals don’t have rapid bilirubin testing. Without a quick result, doctors guess. And guessing kills.

- Outdated protocols. Some clinics still use old guidelines that don’t mention medication risk. Training hasn’t caught up.

The FDA has had a black box warning on sulfonamide labels since 2007: "Avoid use in neonates and infants under 2 months." But warnings on a bottle don’t change practice. Systems do.

The Future: What’s Changing

The NIH awarded $2.4 million in February 2023 to develop point-of-care devices that measure free bilirubin - not just total. That’s a game-changer. Imagine a handheld device that tells you, right at the bedside, how much bilirubin is floating free. No waiting. No guesswork.Hospitals are also improving. In 2015, only 42% of U.S. hospitals had protocols to screen for medication risks. By 2023, that number jumped to 78%. Academic centers are ahead - they’re 3.7 times more likely to have automated alerts than community hospitals. But the gap is still wide.

For now, the rule is simple: if a newborn has jaundice, don’t give sulfonamides. Don’t give aspirin. Don’t give ceftriaxone unless you’ve checked the bilirubin and albumin. Use alternatives. Ask for help. Double-check.

Kernicterus doesn’t have to happen. It’s not a tragedy of biology. It’s a tragedy of oversight. And we know how to stop it.

Can a newborn have kernicterus even if their bilirubin level looks normal?

Yes. Total serum bilirubin can appear within the "normal" range while the free (unbound) bilirubin level is dangerously high. This often happens when medications like sulfonamides displace bilirubin from albumin. A baby with a bilirubin of 13 mg/dL and low albumin (below 3.0 g/dL) may be at greater risk than a baby with 16 mg/dL but high albumin. That’s why checking albumin and knowing medication history matters more than the total number alone.

Are all antibiotics dangerous for jaundiced newborns?

No. Only certain ones that displace bilirubin from albumin. Sulfonamides, ceftriaxone, and aspirin are high-risk. But amoxicillin, penicillin, and most cephalosporins (except ceftriaxone) are safe. Always check the drug’s effect on bilirubin binding. If in doubt, choose an alternative.

Why is G6PD deficiency a concern with sulfonamides?

G6PD deficiency causes red blood cells to break down faster when exposed to certain drugs, including sulfonamides. This leads to a sudden spike in bilirubin production. In a jaundiced newborn, this can push bilirubin levels into the danger zone within hours. Screening for G6PD is critical in populations with higher prevalence - such as those of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian descent.

Is it safe to give sulfonamides to a newborn if they’re not jaundiced yet?

No. Jaundice can develop rapidly - often within 12 to 24 hours after a drug is given. The AAP recommends avoiding sulfonamides in any infant under 2 months if bilirubin is above 75% of the phototherapy threshold, regardless of whether jaundice is visible. Prevention is based on risk, not symptoms.

What should parents do if their newborn is prescribed a sulfonamide?

Ask two questions: 1) Has the baby’s bilirubin level been checked? 2) Is there a safer antibiotic available? If the answer to either is no, ask for a second opinion. Parents are not expected to know the pharmacology - but they should feel empowered to ask. Many preventable cases happen because no one questioned the order.

12 Comments

This is exactly why we need standardized protocols. Sulfonamides in newborns should be banned outright. The data is clear, the risks are known, and the alternatives are cheap and safe. No more guessing.

I work in a rural clinic and this post hit home. We just got a new bilirubin meter last month. It’s not perfect but it’s changed everything. Parents are scared. We’re scared. But now we’re not guessing anymore.

The AAP guidelines are laughably conservative. If you're still using sulfonamides at all, you're already failing. The real problem isn't the drug-it's the system that lets doctors think they're doing good while quietly poisoning babies.

Let’s be real: 87% reduction with EHR alerts? That means 13% of hospitals are still doing this wrong. And those 13%? They’re the ones with the worst outcomes. The fact that we still have hospitals without rapid bilirubin testing in 2024 is a national disgrace. Someone needs to lose their license over this.

Thank you for this detailed, evidence-based breakdown. I’m a nurse practitioner and I’ve seen too many near-misses. We need more education, not just for physicians but for midwives, residents, and even pharmacists. This isn’t niche-it’s foundational.

I’m from the Philippines and we still use sulfonamides like candy. One time I saw a 3-day-old on sulfisoxazole for a "preventive" ear infection. Mom didn’t know any better. No one asked about bilirubin. No one checked albumin. It’s terrifying how normal this is outside the US.

So let me get this straight. We have a drug that can cause permanent brain damage in newborns… and we still prescribe it because it’s 50 cents? The real tragedy isn’t the medical error. It’s the economics that value a dime over a child’s future.

There’s a deeper philosophical layer here. We treat bilirubin like a number, when it’s really a symptom of a system failure. The body isn’t broken. The system is. We measure, we label, we quantify-but we don’t listen. The baby doesn’t care about the threshold. It just wants to survive.

I’m a pediatric resident. I didn’t learn this until my third rotation. The curriculum barely mentions drug displacement. We’re trained to treat symptoms, not to interrogate the pharmacology behind the order. This post should be mandatory reading for every med student.

I’m so glad someone finally said this. My cousin’s baby had kernicterus. They gave Bactrim because the doctor said it was "just a precaution." No bilirubin test. No warning. Now he’s 4 and needs speech therapy. It’s not a rare case. It’s a quiet epidemic.

G6PD + sulfonamides = ticking time bomb. In India, we screen for G6PD in 90% of newborns now. But in rural areas? Still no. We need mobile units. We need community health workers. We need to stop waiting for hospitals to fix this.

The real villain isn’t the drug. It’s the arrogance of medicine. We think we know better. We think we can manage risk. But when a baby’s brain turns yellow, there’s no second chance. Prevention isn’t a protocol. It’s a moral imperative.