Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome Diagnostic Calculator

Diagnostic Criteria

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is characterized by:

- Severely elevated fasting gastrin (>1,000 pg/mL)

- Extremely low gastric pH (<1.0)

- Paradoxical rise in gastrin during secretin stimulation test (>120 pg/mL increase)

Imagine a tiny tumor that turns the stomach into a fire‑hose of acid. That’s the core problem in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Understanding why the acid goes rogue helps doctors spot the disease early and choose the right treatment.

What is Zollinger‑Ellison Syndrome?

When you first hear the name, you might think it’s just another ulcer condition. In reality, Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome is a rare disorder caused by a gastrin‑producing neuroendocrine tumor, called a gastrinoma, that usually sits in the pancreas or duodenum. The tumor secretes excessive gastrin, which in turn drives the stomach’s acid‑producing cells into overdrive.

The Hormonal Engine: Gastrin and G‑cells

The stomach lining contains G‑cells, specialized endocrine cells located mainly in the antrum. Their job is to release gastrin, a peptide hormone that tells the parietal cells to secrete hydrochloric acid. Under normal conditions, gastrin release is tightly regulated by stomach pH, food intake, and neural signals.

In Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome, the gastrinoma produces gastrin independent of these checks. Blood gastrin levels can climb to >1,000 pg/mL-well above the 100 pg/mL upper limit for healthy adults.

Gastrinoma: The Tumor That Won’t Quit

A gastrinoma is a type of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET). Most are well‑differentiated and benign‑appearing on imaging, yet they behave aggressively because of the hormone they dump into the bloodstream.

These tumors often arise from the embryologic foregut, which explains why they can be found in the duodenum, pancreas, or even the lymph nodes nearby. Their growth rate is usually slow, but the hormonal impact is rapid and severe.

Acid Hypersecretion Mechanics

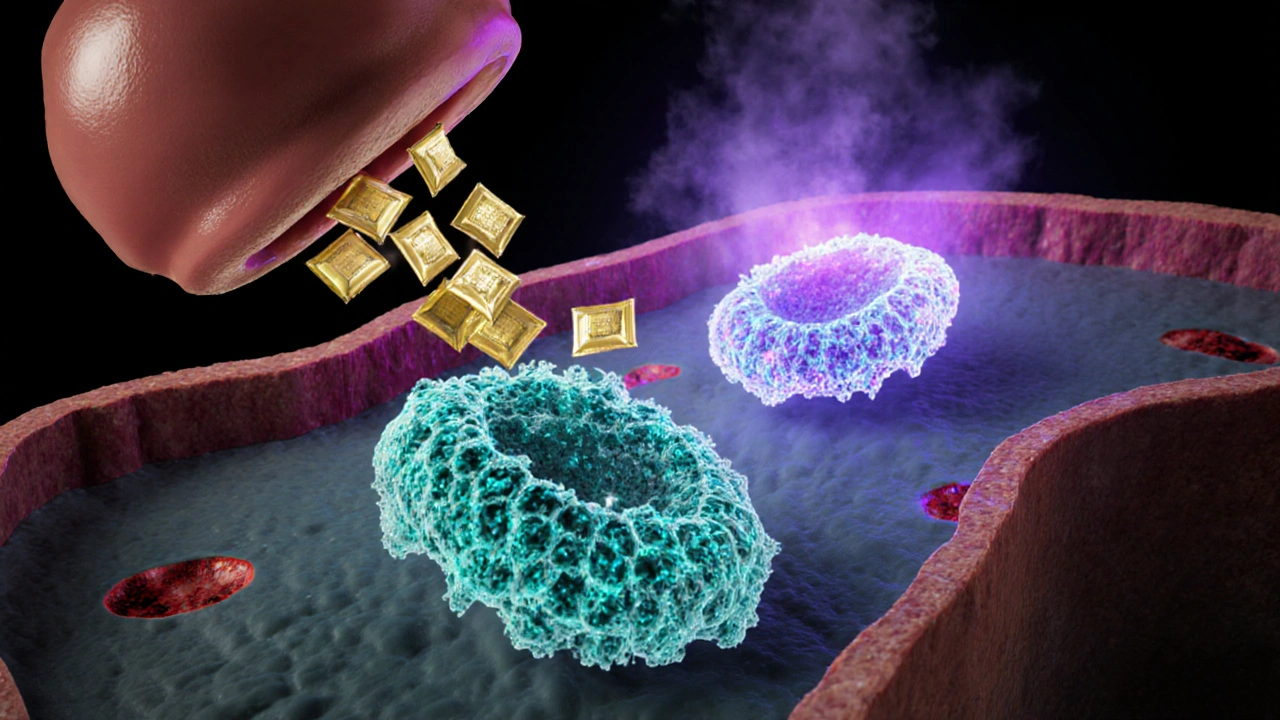

Once gastrin floods the circulation, it binds to CCK‑B receptors on parietal cells. This triggers a cascade that ultimately activates the H⁺/K⁺‑ATPase-the proton pump responsible for pumping hydrogen ions into the stomach lumen.

The result? Gastric pH can drop below 1.0, a level that would normally kill most ingested microbes. This extreme acidity erodes the mucosal barrier, leading to multiple, refractory peptic ulcers that often appear beyond the duodenal bulb, in the jejunum, or even the ileum.

Clinical Fallout: Ulcers, Diarrhea, and Malabsorption

Constant acid exposure overwhelms the protective mucus layer, producing:

- Recurrent duodenal and jejunal ulcers that fail to heal with standard therapy.

- Acid‑induced diarrhea-when too much acid reaches the small intestine, it inactivates pancreatic enzymes and damages the villi, causing steatorrhea and nutrient loss.

- Gastric dumping syndrome, where rapid gastric emptying worsens abdominal cramping.

Patients may present with unexplained weight loss, anemia from chronic bleeding, or even osteoporosis due to calcium malabsorption.

Genetic Connections: MEN‑1 and Other Mutations

About 20‑30% of Zollinger‑Ellison cases are linked to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN‑1), an inherited syndrome caused by mutations in the MEN1 gene. MEN‑1 patients often develop parathyroid hyperplasia, pituitary adenomas, and gastrin‑producing tumors.

Even in sporadic cases, somatic mutations in the RET proto‑oncogene or the KRAS pathway have been reported, underscoring the genetic heterogeneity of gastrinomas.

How doctors confirm the diagnosis

The classic work‑up hinges on two pillars: hormone measurement and functional testing.

- Serum gastrin level: A fasting gastrin >1,000 pg/mL is highly suggestive, especially when paired with low gastric pH.

- Secretin stimulation test: In most people, secretin suppresses gastrin. In Zollinger‑Ellison, secretin paradoxically raises gastrin >120 pg/mL within 2‑10 minutes. This paradox is captured in the secretin test.

Imaging (CT, MRI, endoscopic ultrasound, and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy) helps locate the gastrinoma for surgical planning.

From Pathophysiology to Treatment

Understanding the acid loop directs therapy:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): By directly blocking the H⁺/K⁺‑ATPase, high‑dose PPIs normalize gastric pH and allow ulcers to heal.

- Somatostatin analogues: Agents like octreotide bind to somatostatin receptors on gastrinomas, curbing gastrin release.

- Surgical resection: When the tumor is localized, removing it can cure the hypergastrinemia.

Even after surgery, many patients remain on lifelong PPIs because microscopic disease can persist.

Quick Takeaways

- Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome is driven by a gastrin‑secreting neuroendocrine tumor (gastrinoma).

- Excess gastrin overstimulates parietal cells via the H⁺/K⁺‑ATPase, pushing gastric pH below 1.

- Resulting acid overload creates refractory ulcers, diarrhea, and nutrient malabsorption.

- Up to one‑third of cases are linked to MEN‑1; genetics play a notable role.

- Diagnosis relies on markedly elevated fasting gastrin and a paradoxical secretin stimulation test.

| Feature | Normal Range | Zollinger‑Ellison Range |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting gastrin (pg/mL) | ≤100 | >1,000 (often >2,000) |

| Gastric pH | 1.5-3.5 (fasting) | <1.0 |

| Secretin‑induced gastrin rise (pg/mL) | ↓ or unchanged | ↑ ≥120 within 10min |

| Number of ulcers | None or single duodenal ulcer | Multiple, refractory, often distal to duodenum |

Frequently Asked Questions

What triggers the secretin stimulation test to show a rise in gastrin?

In Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome, gastrin‑producing tumor cells express atypical CCK‑B receptors that respond to secretin with increased gastrin release, opposite to the normal suppressive effect.

Is Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome inherited?

Approximately 20‑30% of cases are part of MEN‑1, an autosomal‑dominant syndrome. The remaining cases are sporadic, though somatic mutations can still be identified in the tumor tissue.

Can PPIs cure Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome?

PPIs control acid output and heal ulcers but do not eliminate the underlying gastrinoma. Long‑term therapy is usually required unless the tumor is surgically removed.

Why do patients often develop diarrhea?

Excess acid reaching the small intestine inactivates pancreatic enzymes and damages the mucosa, leading to malabsorption and watery stools.

What imaging modality is best for locating gastrinomas?

Endoscopic ultrasound provides high resolution for small pancreatic lesions, while Ga‑68 DOTATATE PET/CT excels at detecting somatostatin‑receptor positive tumors throughout the abdomen.

10 Comments

The hypersecretion cascade in Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome initiates when gastrin binds to CCK‑B receptors on parietal cells, activating the phospholipase C pathway and culminating in H⁺/K⁺‑ATPase up‑regulation. This mechanistic surge drives intragastric pH below 1, which overwhelms mucosal defenses and precipitates refractory peptic ulceration. Elevated gastrin also exerts trophic effects on enterochromaffin‑like cells, perpetuating a paracrine loop of acid production. Clinically, the paradoxical secretin response serves as a functional biomarker distinguishing gastrinomas from other hypergastrinemic states. Therapeutic suppression therefore targets both the proton pump and the gastrin ligand‑receptor interaction.

Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome results from a gastrin‑producing tumor that pushes fasting gastrin levels well above the normal ceiling, often exceeding 1,000 pg/mL. The excess hormone forces the stomach to secrete acid at rates that normal medications can’t always tame. A secretin stimulation test that shows a rise in gastrin instead of suppression clinches the diagnosis. Imaging modalities such as CT, MRI, or somatostatin receptor scintigraphy are then employed to locate the gastrinoma. Early surgical resection, when feasible, can eradicate the source of hypergastrinemia.

Managing this condition starts with high‑dose proton pump inhibitors to neutralize the acid flood, which gives ulcer sites a chance to heal. Concurrently, somatostatin analogues like octreotide can blunt gastrin release from the tumor. Patients should be counseled that lifelong medication may be necessary even after tumor removal because microscopic disease can linger. Nutritional support, especially calcium and vitamin D supplementation, helps offset malabsorption from acid‑induced diarrhea. Regular monitoring of gastrin levels and periodic imaging are essential components of long‑term care.

First off, let me say that the interplay between gastrin excess and acid hypersecretion is nothing short of a perfect storm for the gastrointestinal tract, and it’s easy to underestimate just how far‑reaching the consequences can be. When you have a gastrinoma churning out hormone in an unregulated fashion, the parietal cells become revved up like a high‑performance engine, and the resulting pH plunge can drop below one, a level that would normally vaporize most ingested pathogens. This relentless acid barrage doesn’t just eat away at the mucosal lining; it also inactivates pancreatic enzymes once it reaches the duodenum, which explains why patients often develop steatorrhea and fatty‑soluble vitamin deficiencies. The chronic ulcerations aren’t confined to the duodenal bulb either; they can wander into the jejunum or even the ileum, making endoscopic detection a bit of a treasure hunt. From a diagnostic standpoint, the secretin stimulation test is a real clincher because the paradoxical rise in gastrin flips the usual physiology on its head, and that’s something you can’t ignore. Imaging plays a crucial role, especially somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, which lights up the gastrinoma with a glow that’s hard to miss on conventional CT or MRI scans. On the therapeutic side, high‑dose PPIs are the first line, effectively turning down the acid faucet, but they’re not a cure‑all; many patients still need somatostatin analogues to tame the hormone source. When the tumor is localized and resectable, surgery offers the best chance at a cure, yet even then, microscopic seeds can seed the liver or lymph nodes, so vigilant follow‑up is non‑negotiable. Don’t forget the genetic angle-up to a third of cases are linked to MEN‑1, and a thorough family history can flag relatives who might benefit from early screening. Lifestyle tweaks, like avoiding NSAIDs and limiting alcohol, can reduce additional mucosal irritation, while a diet rich in alkaline foods may help buffer the excess acid a bit. Lastly, the psychosocial impact shouldn’t be brushed aside; dealing with chronic disease, frequent doctor visits, and the possibility of lifelong medication can be mentally draining, so encouraging patients to seek support groups or counseling can make a world of difference. All in all, a multidisciplinary approach that combines endocrinology, gastroenterology, surgery, and nutrition is the gold standard for navigating this complex syndrome.

The genetic work‑up for MEN‑1 should be ordered early, because identifying a hereditary pattern can streamline surveillance for the whole family. Also, consistent high‑dose PPIs are a must to keep the acid under control.

Basically, crank up the PPI dosage until the ulcer pain eases, then keep the meds on board for life if the tumor can’t be fully removed. It’s not glamorous, but it works.

Some people find that spacing meals smaller throughout the day can lessen the acid spikes, though results vary from person to person.

That's a solid tip, Ryan; I’d add that pairing the PPI with a timed H2 blocker before meals can give an extra layer of protection for those who still experience breakthrough symptoms.

From a molecular standpoint, MEN1‑associated gastrinomas often harbor loss‑of‑function mutations in the menin tumor suppressor, leading to unchecked transcription of gastrin gene promoters; this underlines the necessity of integrating genetic counseling into the standard diagnostic algorithm.

Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome may be rare, but its impact on quality of life is massive.