Acid Hypersecretion: What It Is and Why It Matters

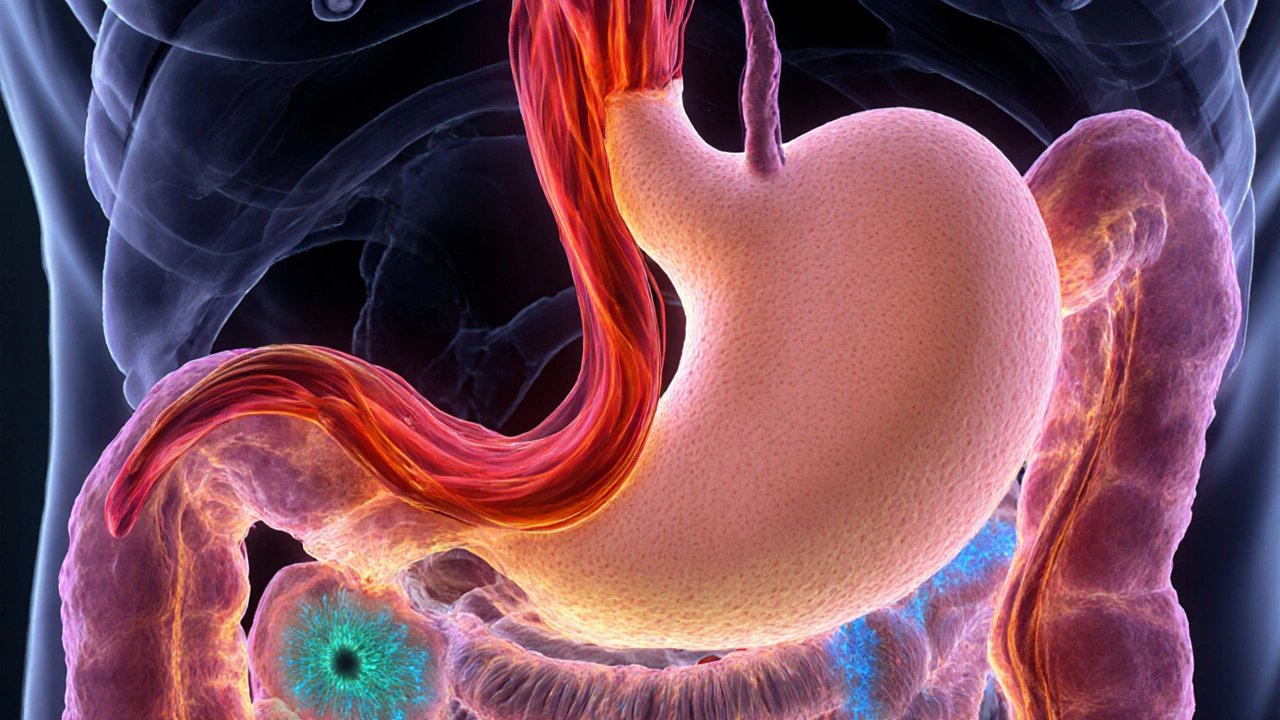

When dealing with acid hypersecretion, the stomach produces more acid than normal, often leading to discomfort and damage to the digestive lining. Also known as excess stomach acid, it can trigger a range of problems from occasional heartburn to serious ulcers.

Why Your Stomach Might Go into Overdrive

The stomach’s acid output is tightly controlled by hormones and signaling molecules. Gastrin, a hormone released by G‑cells in the stomach lining, tells the parietal cells to crank up acid production. When gastrin levels rise abnormally—because of tumors, chronic inflammation, or certain medications—the result is a surge in acid. Histamine, another key player, binds to H2 receptors on the same cells, further boosting acid output. Together, these signals can push the stomach into a constant state of hypersecretion.

Two of the most common clinical pictures linked to this process are GERD, gastro‑esophageal reflux disease, where acid frequently backs up into the esophagus and peptic ulcer disease, ulcers that form in the stomach or duodenum due to acid‑induced tissue erosion. Both conditions share the root cause of too much acid, but they manifest differently—GERD shows up as burning chest pain, while ulcers cause gnawing stomach pain and sometimes bleeding.

Symptoms of acid hypersecretion are often easy to spot. The classic “heartburn” feeling of a sour taste rising up the throat is a hallmark of reflux. Others include regurgitation of food, bloating, nausea, and a sour‑tasting breath. In severe cases, patients may notice black or tarry stools, a sign of gastrointestinal bleeding from an ulcer.

Doctors confirm excessive acid through a few reliable tests. An upper endoscopy lets them look directly at the esophagus and stomach lining, spotting erosions or ulcerations. 24‑hour pH monitoring measures acid exposure in the esophagus, giving an objective readout of reflux severity. Blood tests for gastrin levels can also pinpoint hormonal overproduction.

When it comes to calming the acid flood, several medication classes are available. Proton pump inhibitors, commonly called PPIs, block the final step of acid production in parietal cells, offering the strongest acid suppression are the go‑to for most patients with severe reflux or ulcer disease. H2 blockers, such as ranitidine or famotidine, work earlier in the pathway by stopping histamine from stimulating acid release. For occasional relief, antacids, quick‑acting tablets that neutralize existing stomach acid, can be useful after meals. Choosing the right drug often hinges on how often symptoms appear, how severe they are, and whether any underlying conditions (like H. pylori infection) need treatment.

Medication isn’t the whole story, though. Lifestyle tweaks can reduce the trigger load on the stomach. Eating smaller, more frequent meals, avoiding late‑night snacks, and steering clear of known irritants—spicy foods, caffeine, alcohol, and high‑fat meals—can lower acid spikes. Maintaining a healthy weight also helps; excess abdominal pressure pushes stomach contents up into the esophagus, worsening reflux.

Now that you’ve got a solid grasp of what drives acid hypersecretion, how it shows up, and the toolbox for tackling it, you’re ready to explore the detailed guides below. From side‑by‑side drug comparisons to practical tips for dining out without heartburn, the collection ahead breaks down each aspect into clear, actionable advice.

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome Pathophysiology Explained

Explore how gastrin‑producing tumors drive extreme acid secretion in Zollinger‑Ellison syndrome, its genetic links, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

Keep Reading