Imagine taking a medication meant for once a day-four times a day. Not because you misunderstood, but because the doctor wrote QD and the pharmacist read it as QID. That’s not a hypothetical. It’s happened. And it’s still happening.

In 2023, a patient in Melbourne was admitted to hospital after taking warfarin four times daily instead of once. Her INR spiked to 12.3-life-threateningly high. The prescription said 1 tab QD. The pharmacy label said take four times daily. No one caught it until she collapsed.

This isn’t rare. It’s systemic. And it’s avoidable.

What QD and QID Really Mean (And Why They’re Dangerous)

QD stands for quaque die-Latin for “once daily.” QID means quater in die-“four times daily.” These abbreviations have been around for centuries. But in modern healthcare, they’re outdated, ambiguous, and deadly.

The problem isn’t just that they look similar. It’s that they’re written in messy handwriting, typed on small screens, or misread under pressure. A nurse might see QD and think QID. A pharmacist might assume the doctor meant four doses because the drug is “strong.” A patient might not speak English well and just trust the label.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, about 5% of all medication errors reported to MedWatch involve confusing abbreviations like QD and QID. That’s not a small number. That’s thousands of incidents every year.

And the consequences? Sedation. Low blood pressure. Bleeding. Hospitalizations. Death.

Real Cases, Real Harm

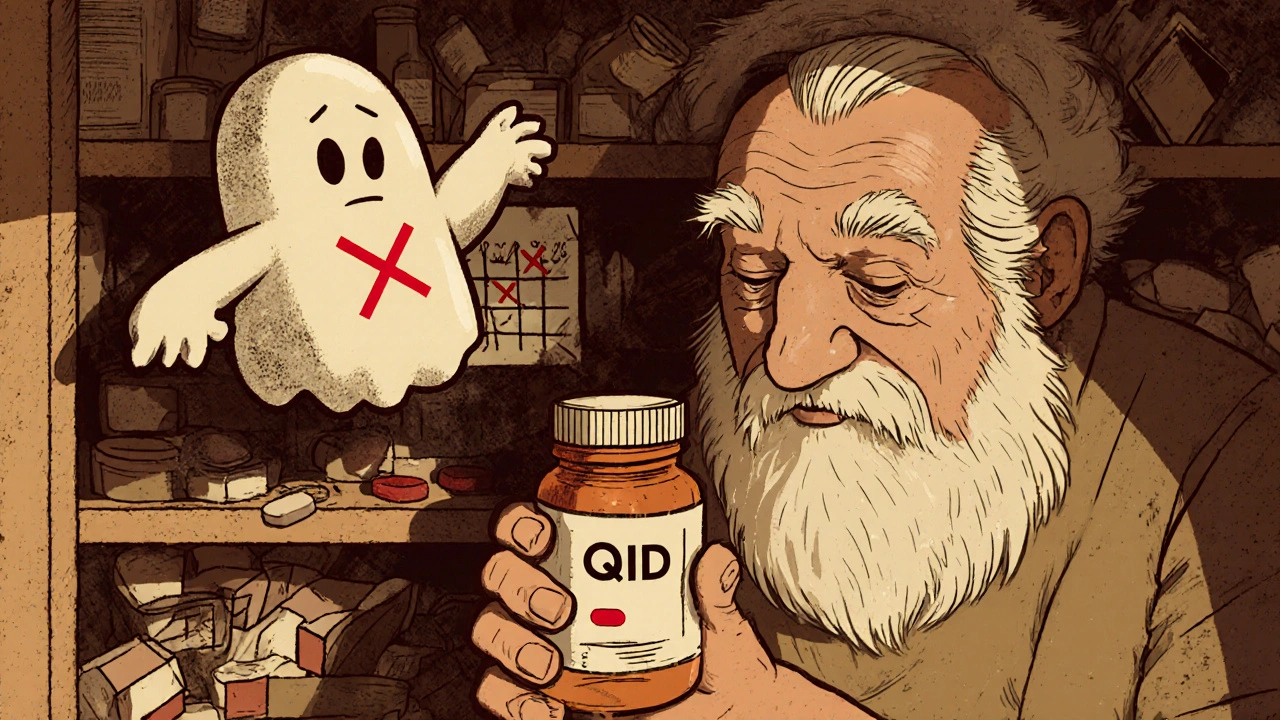

In 2021, a 72-year-old man in Minnesota was prescribed a blood pressure pill to be taken once daily. The prescription read “QD.” The pharmacy dispensed it with instructions to take it four times a day. He did. For three weeks. His blood pressure dropped to 80/50. He passed out while walking his dog. He broke his hip.

That same year, a nurse in California reported a case where a patient took a sedative four times daily instead of once. She kept working as a construction inspector. She drove her 7-year-old daughter to school every morning. She didn’t realize anything was wrong until she ran out of pills and asked for a refill.

These aren’t outliers. A 2018 study in the Journal of Patient Safety found that QD was misread as QID in 12.7% of simulated prescription reviews. Among staff with less than five years of experience? It jumped to 18.2%.

And it’s not just hospitals. Community pharmacies intercept an average of 2.7 QD/QID errors per week. That’s one every other day.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Older adults are the most vulnerable. People over 65 make up 68% of documented cases of QD/QID confusion. Why? They’re often on five, six, even ten medications. Their vision may be poor. Their memory may be fading. They don’t always ask questions.

Patients with limited health literacy are also at high risk. If you’ve never seen “QD” before, you have no idea what it means. You might assume it’s “every day,” but you won’t know if that’s once or four times.

And here’s the worst part: patients don’t always tell you when they’re confused. A 2021 survey by the National Patient Safety Foundation found that 63% of patients admitted they’d been unsure about their dosing instructions at least once. QD vs. QID ranked as the third most confusing instruction-right after “take with food” and “take on empty stomach.”

Why Do These Abbreviations Still Exist?

You’d think by now, everyone would’ve stopped using them. But they haven’t.

In 2015, the American Medical Association found that 30% of handwritten prescriptions still used QD and QID. Even today, 31% of community pharmacies in the U.S. still get handwritten scripts with these abbreviations-from doctors who don’t use electronic systems.

Some providers say it’s faster. “QD” takes two seconds to write. “Once daily” takes five. But that five seconds could save a life.

Electronic health record (EHR) systems have helped. By 2022, 87% of EHRs had built-in checks to block QD and QID. But here’s the catch: providers can still override those warnings. And when they do, errors still happen. A 2021 analysis found that 3.8% of errors in EHR systems came from manual overrides.

And even when systems block the abbreviations, some providers still type them in notes, or say them out loud. “Give it QD.” Then someone else hears it wrong.

What Should You Write Instead?

The fix is simple: write it out.

Instead of QD, write: once daily.

Instead of QID, write: four times daily.

It’s not harder. It’s clearer. And it’s safer.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has been saying this since 2001. The Joint Commission added QD and QID to their “Do Not Use” list in 2004. The FDA, WHO, and American Hospital Association all agree: these abbreviations must go.

In 2023, the American Medical Association updated its guidelines to require writing out dosing instructions in plain language. Epic and Cerner-two of the biggest EHR vendors-now block QD and QID entirely. If you type them, the system won’t let you save the prescription.

And it’s working. Hospitals that banned these abbreviations saw a 42% drop in dosing errors within a year.

How to Prevent These Errors-Five Proven Steps

Preventing QD/QID errors isn’t about blaming individuals. It’s about fixing systems.

- Eliminate all abbreviations for dosing frequency. Never use QD, QID, BID, TID. Write out “once daily,” “twice daily,” “three times daily,” “four times daily.”

- Use computer alerts. If a provider tries to prescribe a drug that’s usually taken once daily but enters “four times daily,” the system should pop up: “Are you sure? This medication is typically dosed once daily.”

- Train staff to ask open-ended questions. Don’t ask, “Is this QD or QID?” Ask, “How often are you supposed to take this pill?” That forces the patient to explain in their own words.

- Standardize labels with icons. Add a small visual: one pill with a clock for “once daily,” four pills with clocks for “four times daily.” Pictures stick better than words for many people.

- Require verbal verification. Every new prescription should be reviewed aloud with the patient. “This is your blood pressure pill. You take one tablet every morning, right?” That simple check reduced errors by 67% in one university hospital study.

These steps don’t cost a fortune. A community hospital can implement them for $8,500-$12,000. The return on investment? $8.70 saved for every $1 spent.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Medication errors cost the U.S. healthcare system $2.1 billion a year. $780 million of that comes from dosing frequency mistakes-mostly because of QD and QID.

And it’s not just money. It’s trust. It’s dignity. It’s someone’s ability to live safely at home.

The National Action Alliance for Patient Safety launched the “Clear Communication Campaign” in April 2023 with $45 million in funding. Their goal? Reduce abbreviation-related errors by 90% by 2026.

And they’re not alone. In June 2023, the FDA released draft guidance saying Latin abbreviations should no longer be used on prescriptions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services now penalize hospitals with high error rates. Insurance companies are starting to tie reimbursement to safety metrics.

This isn’t just a clinical issue. It’s a moral one.

What Patients Can Do

You don’t have to wait for the system to fix itself. Here’s what you can do right now:

- Ask your doctor: “Can you please write out how often I’m supposed to take this?”

- When you get your prescription, read the label. Does it say “once daily” or “QD”? If it says QD, ask the pharmacist to explain it.

- Use a pill organizer with clear labels. Put the days of the week on it.

- Keep a list of all your medications and their dosing schedules. Bring it to every appointment.

- If you’re unsure, call your pharmacist. They’re trained to catch these errors. Don’t be afraid to ask.

One patient told me: “I didn’t know what QD meant. I thought it was ‘quick dose.’ I took it four times. I didn’t realize I was overdosing until I felt dizzy all day.”

That’s not your fault. It’s the system’s.

But you can protect yourself. And you can demand better.

The Future Is Clear

There’s no excuse anymore. We have technology. We have guidelines. We have proof that writing out “once daily” saves lives.

QD and QID are relics. They belong in medical history books-not on prescriptions.

Every time you write out the full phrase, you’re not just following a rule. You’re preventing a tragedy.

And that’s not just good practice. It’s the bare minimum we owe to every patient who trusts us with their health.

9 Comments

i literally had a friend almost die from this. her doc wrote 'QD' for her blood thinner and the pharmacy gave her a label that said '4x daily.' she took it for a week before her gums started bleeding out. she didn't even know what QD meant. no one asked. no one checked. just assumed. this isn't a 'medical error'-it's a failure of basic human care.

Let’s be real-this isn’t about abbreviations. It’s about the collapse of intellectual rigor in medicine. We’ve outsourced thinking to EHRs and assumed automation fixes stupidity. QD and QID aren’t the problem. The problem is that clinicians stopped thinking in Latin because they stopped thinking at all. The real tragedy? We’re still surprised when people die because we stopped teaching precision and started rewarding speed.

so we’re spending millions to replace two letters with four words? cool. next up: banning ‘etc.’ because someone might think it means ‘eat the cat.’

my grandma took her meds wrong for 3 months because of QD. she didn’t say anything because she didn’t want to ‘bother’ anyone. when she finally told us, she was in the hospital, shaking, confused, scared. she just kept saying ‘I thought it meant every day… I didn’t know it meant once.’ i cried for two days. this isn’t policy. this is family trauma. please just write it out. it takes 5 seconds. 5 seconds could’ve saved her dignity.

The data here is overwhelming and the solutions are practical, low-cost, and evidence-based. Eliminating ambiguous abbreviations isn’t just a safety protocol-it’s a professional obligation. The fact that this is still an issue in 2024 reflects a gap in institutional accountability, not a lack of knowledge. Hospitals that have implemented plain-language policies report not only fewer errors but also higher patient satisfaction scores. It’s a win-win. The question isn’t whether we can afford to change-it’s whether we can afford not to.

USA got the best healthcare system in the world, but we still let doctors write like they’re in 1890? I bet in China they just use AI to auto-correct everything. Meanwhile we’re still arguing over whether ‘QD’ is ‘quack’ or ‘quiet.’

you think this is bad? wait till you hear about the woman who took ‘BID’ as ‘beid’ and thought it was a brand name. she went to the store and asked for ‘Beid pills.’ the pharmacist laughed at her. then she had a stroke. now she’s suing everyone. and no one even apologized. this is why I don’t trust doctors. they don’t care. they just want to get through their charting.

thank you for writing this. 🙏 i work in a pharmacy and we catch 2-3 QD/QID errors a week. most patients don’t even know to question it. i always say ‘can I read this back to you?’ and 90% of the time they say ‘oh wow, I thought it was four times.’ i wish every prescriber had to shadow a pharmacist for a day. it changes everything. 🏥❤️

It is with profound regret that I observe the persistent anachronism of Latin medical nomenclature within the modern Anglo-American clinical framework. The persistence of such archaic conventions-QD, QID, TID-represents not merely a lapse in communication, but a systemic dereliction of professional duty. In the United Kingdom, such practices were formally abolished in NHS guidelines as early as 2006. The continued use of these symbols in the United States is not merely negligent; it is an affront to the principles of patient safety upon which modern medicine claims to be founded. I urge all stakeholders to adopt the British standard without delay. This is not a suggestion. It is a moral imperative.