When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you probably assume it’s cheap because competition keeps prices low. But what if that low price suddenly jumps 300% overnight? That’s not a glitch-it’s how the system works when there’s no real government control over generic drug prices in the U.S.

Why Generic Drugs Aren’t Always Cheap

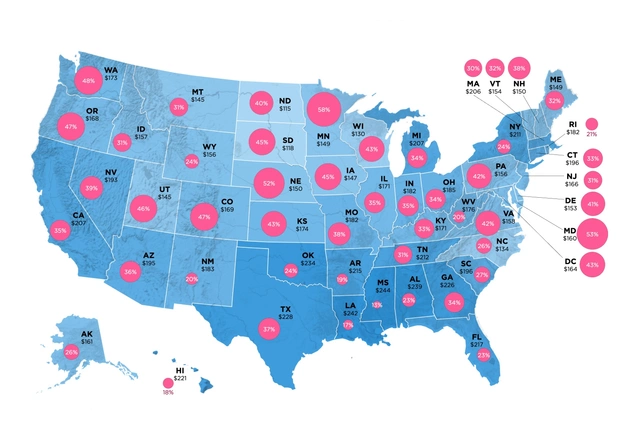

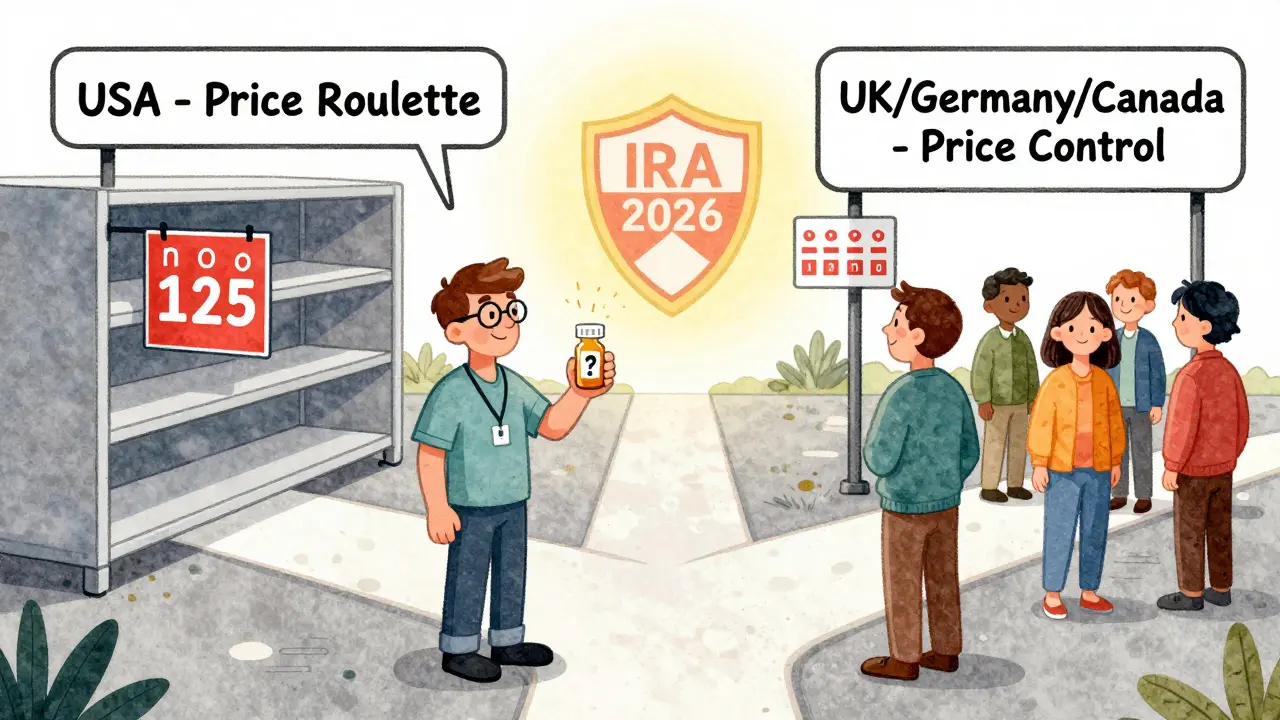

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they account for only 23% of total drug spending. That sounds like a win-until you dig deeper. In 2025, the average price of a generic drug in the U.S. was still 1.3 times higher than in other wealthy countries like Canada, Germany, or the UK. Meanwhile, brand-name drugs cost 3 to 5 times more here than abroad. So why are generics still expensive? The answer isn’t simple. The U.S. doesn’t set prices for generic drugs directly. Instead, it relies on market competition: once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, dozens of manufacturers jump in to make copies. The theory is that competition drives prices down. And it often does-for common drugs like statins or blood pressure meds. But when only two or three companies make a drug, prices can spike. Take pyrimethamine (Daraprim), a treatment for parasitic infections. In 2024, after two manufacturers left the market, the price jumped 300% because no one else was making it. There was no safety net.How the Government Actually Influences Prices

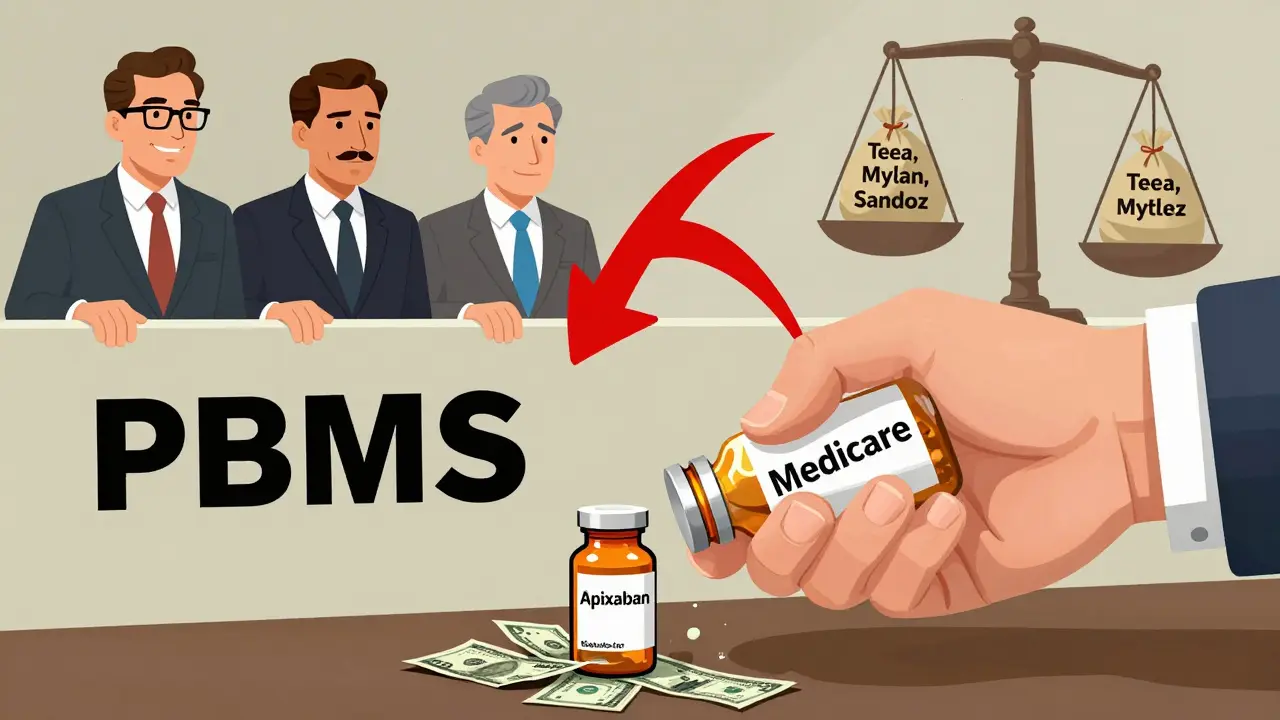

The federal government doesn’t set generic drug prices like a supermarket manager. But it does shape them through powerful programs that force manufacturers to offer discounts. The biggest lever is the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP). Since 1990, drugmakers have been required to pay rebates to Medicaid for every generic drug sold. The rebate is the greater of 23.1% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP), or the difference between AMP and the lowest price offered to any private buyer. In 2024, these rebates totaled $14.3 billion-78% of all Medicaid drug rebates. That money doesn’t go to patients, but it lowers the overall cost to the government. Then there’s the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients get drugs at steep discounts-20% to 50% below AMP. In 2025, 87% of these safety-net clinics reported better patient adherence because patients could finally afford their generic meds. And now, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 has added a new layer. Starting in 2026, Medicare can negotiate prices for a small number of high-cost drugs. While most generics are exempt (because they’re already cheap), the second round of negotiations in 2027 includes generic versions of blood thinners like apixaban and rivaroxaban. These are used by over 5 million Medicare beneficiaries. Analysts expect prices to drop 25-35% once negotiated.What You Pay at the Pharmacy Counter

Your out-of-pocket cost for a generic drug depends on your insurance. For Medicare Part D beneficiaries in 2025:- LIS (Low-Income Subsidy) recipients pay $0 to $4.90 per generic prescription

- Standard beneficiaries pay 25% coinsurance during the initial coverage phase

- Out-of-pocket costs are capped at $2,000 per year-down from over $7,000 before the IRA

Who’s Winning and Who’s Losing

The system works well for big players. Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz control nearly 40% of the generic market. They’ve got the scale to handle complex reporting, negotiate with PBMs, and absorb the costs of Medicaid rebates. But smaller manufacturers? They’re squeezed. Seventy percent of generic drug makers operate on profit margins below 15%. Some can’t afford to make low-volume drugs at all. That’s why rare generic medications-like those for rare diseases or older treatments-keep disappearing or skyrocketing in price. Meanwhile, patients are caught in the middle. A 2025 KFF survey found that 30% of Americans struggle to afford their meds. For 18% of them, it’s the cost of generics-not brand names-that’s the problem.The Global Contrast

Other countries don’t wait for competition to work. They step in. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) negotiates prices directly. In Germany, drugs must prove they’re cost-effective before they’re priced. In Canada, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board sets maximum prices based on what other countries pay. The U.S. system’s strength is speed: 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics because manufacturers can launch fast after patents expire. But the trade-off is instability. Without price ceilings, markets collapse when competition disappears.What’s Changing in 2025-2026

The biggest shift? Medicare’s new power to negotiate prices for select generics. The 2027 list includes apixaban and rivaroxaban-drugs that cost over $40 billion in total spending. If prices drop by 30%, it could save Medicare $12.7 billion over ten years. Also in 2025, new rules forced manufacturers to disclose actual drug costs before dispensing. That’s transparency-but not control. Patients still don’t know what they’ll pay until they reach the counter. And legal battles are brewing. PhRMA sued the government over a proposed Most-Favored-Nation pricing rule that would tie U.S. prices to those in other countries. The lawsuit argues it’s an unconstitutional taking of property. The case is still pending.

What You Can Do

If you’re paying for generics out of pocket:- Use the Medicare Plan Finder to compare plans. Look for tier 1 generics with $0 copays.

- Ask your pharmacist if a different manufacturer’s version is cheaper-even if it’s the same drug.

- Check if your clinic participates in 340B. Many safety-net providers offer generics at near-wholesale prices.

- Use mail-order pharmacies. They often have lower copays for 90-day supplies.